The Neuroscience of Nude Art: How Our Brains Perceive the Human Form

Nude art photography isn’t just a visual experience—it’s a complex neurological process that engages multiple areas of our brain in a fascinating, multilayered dance. Understanding how our brains perceive, recognize, and emotionally process images of the naked human form can provide photographers with powerful insights into their craft. This knowledge can inform and even guide choices in composition, lighting, and posing to create more impactful, memorable images. This comprehensive blog post delves into the neuroscience of art perception and explores how this knowledge can be practically applied to elevate your nude art photography from simple depiction to profound neurological engagement.

The Perceiving Brain: A Tour of How We See the Nude Form

When we view a nude photograph, our brain instantly activates a network of specialized regions, each playing a distinct role in constructing our experience of the image. It’s a cascade of processing that moves from basic shapes to complex emotional and aesthetic judgments in milliseconds.

Initial Processing: The Visual Cortex

Located in the occipital lobe at the back of the brain, the visual cortex is the first stop for all visual data. It acts like a primary analysis engine, breaking down the incoming image into its most basic components: lines, shapes, contrast, orientation, and color. High-contrast edges, like the bright outline of a body against a dark background, create strong signals here, immediately capturing attention. This is the brain’s foundational sketchpad, where the raw geometry of the image is first understood.

Body Recognition: The Fusiform Body Area (FBA)

From the visual cortex, information travels to more specialized regions. Deep within the temporal lobe lies the Fusiform Body Area (FBA), a region expertly tuned to recognize the form and shape of human bodies. It works in concert with the Extrastriate Body Area (EBA), which processes individual body parts. Crucially, studies using fMRI have shown that the FBA responds more strongly to nude bodies than to clothed ones, suggesting a deep, evolutionary importance placed on recognizing the unadorned human form for survival and social bonding.

Emotional Response: The Amygdala

This almond-shaped cluster is the brain’s emotional rapid-response center. It processes core emotions and can trigger an immediate, pre-conscious reaction to a nude image. This “low road” of processing gives a gut reaction—pleasure, fear, curiosity, discomfort—before the conscious mind has even had a chance to apply context. This initial emotional coloring, shaped by the viewer’s cultural programming and personal history, is incredibly powerful.

Context and Judgment: The Prefrontal Cortex

After the amygdala’s initial response, the “high road” of processing engages the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s executive suite. This area is responsible for higher-level cognition, context, and judgment. It analyzes the image’s artistic merit, intent, and cultural meaning. It’s what allows us to override a primal response, distinguish between art and pornography, and make nuanced aesthetic judgments. This region is where appreciation for challenging or unconventional art is formed.

Empathy and Connection: The Mirror Neuron System

This remarkable network of neurons fires both when we perform an action and when we see someone else perform that action. When viewing a pose—whether it’s tense, relaxed, joyful, or pained—our mirror neurons simulate the physical and emotional state of the subject, creating a powerful sense of empathy and embodied connection. We don’t just see the pose; on a neurological level, we *feel* it.

Core Concepts: Translating Neuroscience into Photographic Technique

Understanding these brain processes is not just an academic exercise. Each concept provides a practical pathway to creating more effective photographs that can intentionally guide the viewer’s neurological journey.

The Primacy of the Form: Engaging the Fusiform Body Area (FBA)

The FBA’s heightened sensitivity to the nude form is a gift to photographers. To engage it most effectively, compositions should emphasize the body’s overall shape and contours. In Burak Bulut Yıldırım’s “Great Gatsby,” the lighting is carefully sculpted to define the elegant, S-curve of the model’s back. This clear, uninterrupted depiction of the human form provides a strong, direct signal to the FBA, making the image immediately recognizable and compelling on a primal neurological level. Poses that abstract the body too much can challenge the FBA, forcing the brain to work harder and creating a different, more cognitive experience.

Great Gatsby by Burak Bulut Yıldırım

Feeling the Pose: Embodied Cognition and Mirror Neurons

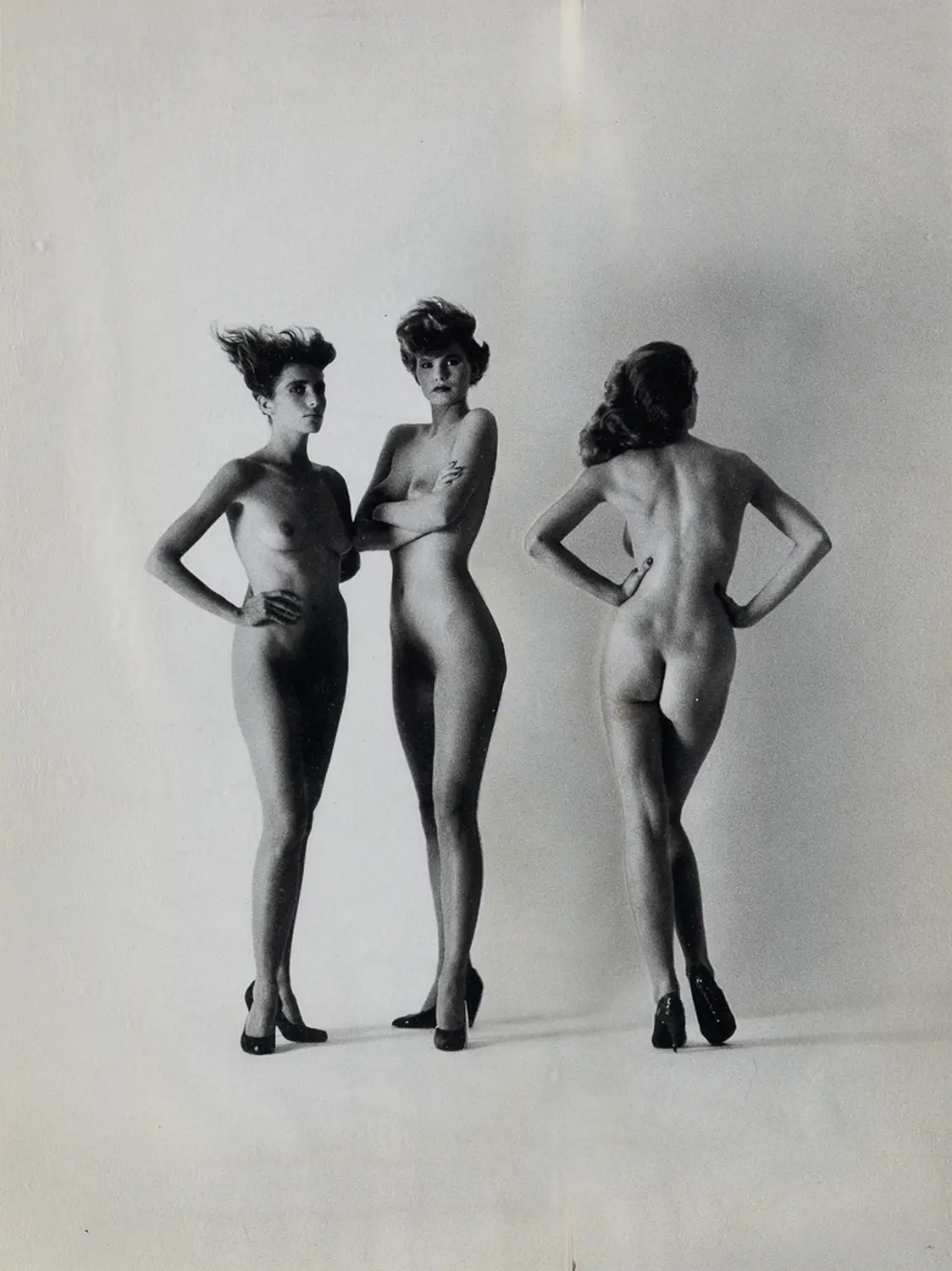

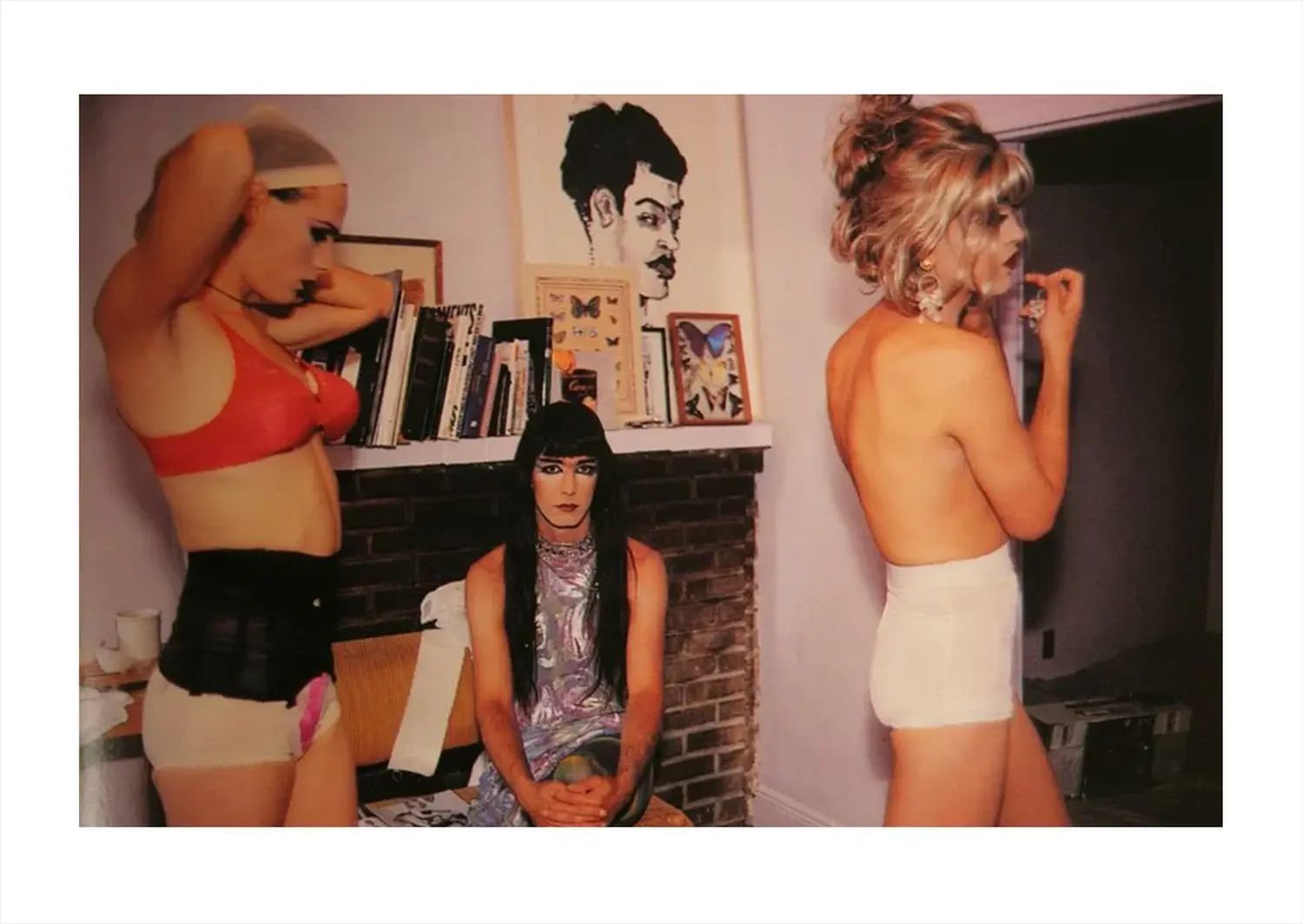

The concept of embodied cognition in art suggests that we understand images by mentally and physically simulating the experiences they depict. Helmut Newton’s work often features models in dynamic, athletic poses. The image below requires significant physical tension and balance. When we view it, our mirror neuron system fires, causing us to subconsciously simulate the strain and power of that pose, creating a visceral, empathetic connection. Similarly, Nan Goldin’s intimate portraits trigger an emotional simulation. We see the subjects’ embrace and our brains mirror the feeling of intimacy and vulnerability, drawing us into the scene’s emotional core. This highlights that mirror neurons respond to both physical actions and emotional states.

Helmut Newton

Nan Goldin

The Science of Beauty: Neuroaesthetics and the Brain’s Reward System

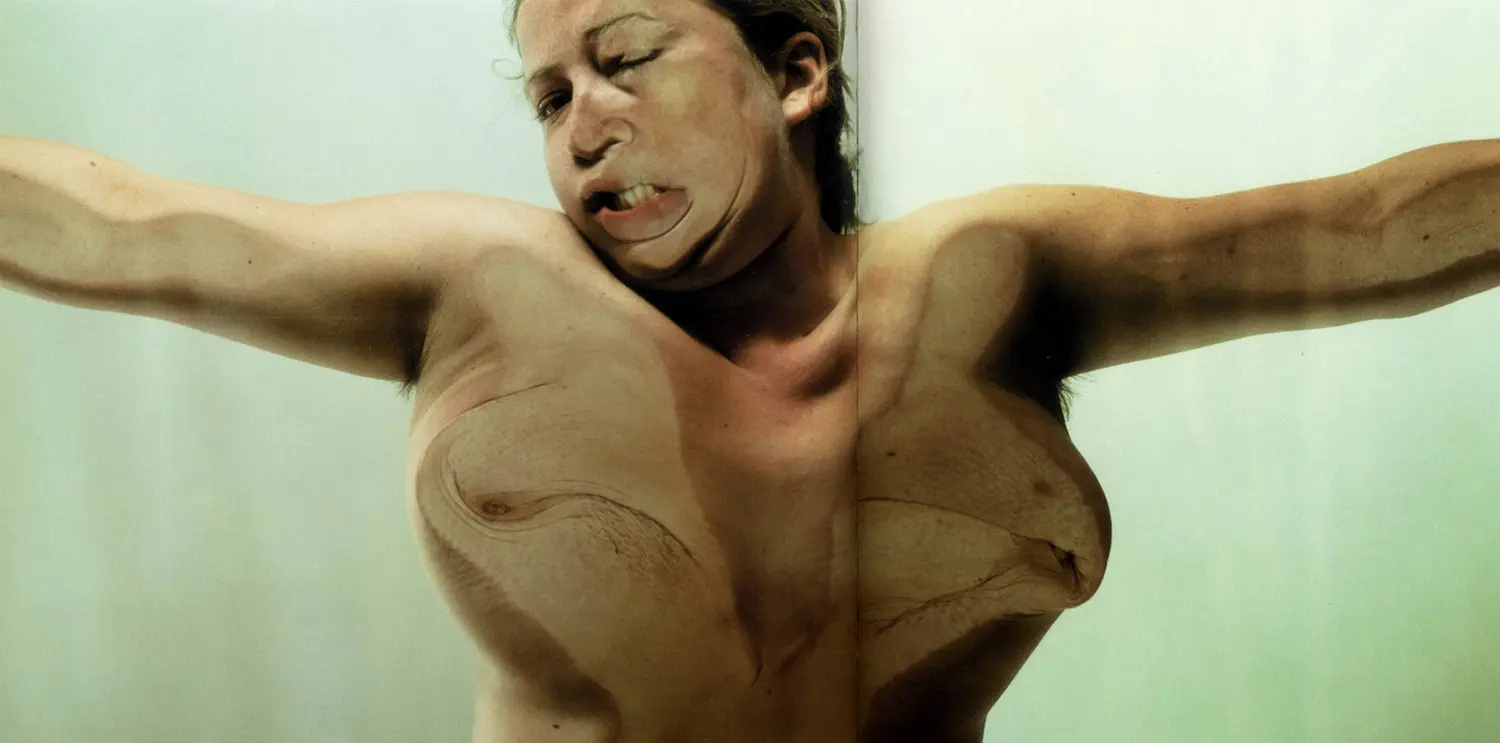

The field of neuroaesthetics studies how our brains respond to beauty. Artworks that we find beautiful can activate reward centers like the nucleus accumbens, giving us a hit of dopamine. Photographers can tap into this in several ways. Bettina Rheims’ glamorous, high-production work uses symmetry, lush colors, and idealized forms that align with conventional beauty standards, directly targeting this pleasure response. In contrast, an artist like Jenny Saville challenges these standards. Her paintings of fleshy, non-idealized bodies might initially confuse the reward system, but they deeply engage the prefrontal cortex, creating a different, more cognitive kind of aesthetic pleasure derived from intellectual challenge, emotional honesty, and the subversion of expectation.

Bettina Rheims

Jenny Saville

Advanced Neuro-Informed Strategies

Beyond the basics, photographers can use more complex neurological principles to create captivating work that holds a viewer’s attention and remains in their memory.

Predictive Coding: The Power of Surprise

Our brains are prediction machines. They constantly build models of the world and predict what they will see next. Art that subverts these predictions creates a powerful “prediction error” signal that commands attention and forces a deeper level of processing. André Kertész’s distorted nudes are a perfect example. The brain predicts a normal human form but is presented with a surreal, elongated one. This violation of expectation forces the brain out of autopilot and into a state of active problem-solving and deep engagement, making the image highly memorable.

André Kertész

Narrative Engagement: The Storytelling Brain

We are wired for story. Images that suggest a narrative engage broad networks across the brain, including memory and language centers. A single image can imply a “before” and an “after.” In Burak Bulut Yıldırım’s “Bride,” the title and the presence of a veil instantly create a narrative frame. The brain begins to ask questions: Why is the bride nude? Is this a moment of vulnerability before the ceremony, or an act of rebellion? This narrative ambiguity is a powerful tool for holding a viewer’s cognitive and emotional attention.

Bride by Burak Bulut Yıldırım

Multisensory Integration: Beyond the Visual

Although photography is visual, it can evoke other senses. Robert Mapplethorpe’s portrait of a subject covered in clay or mud is a powerful example. The rich, wet texture is so vividly rendered that our brain’s somatosensory cortex is activated; we can almost feel the cool, heavy sensation on our own skin. By implying touch, temperature (goosebumps suggesting cold), or even sound (the silence of a vast landscape), photographers can create a richer, more immersive neural experience that goes far beyond sight.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Case Studies: Neuroscience in the Work of Masters

Analyzing master photographers through a neuroscientific lens reveals how they intuitively harnessed these principles to create timeless art.

Spencer Tunick: Overloading the FBA and Creating Patterns

Spencer Tunick’s large-scale nude installations are fascinating from a neurological perspective. By presenting hundreds or thousands of bodies at once, he overwhelms the FBA’s ability to process each one individually. This forces a cognitive shift: the brain stops seeing “bodies” and starts seeing “patterns.” Processing moves from the FBA in the temporal lobe to the parietal cortex, which handles spatial relationships and large-scale patterns. This is why his images are perceived as monumental, abstract landscapes rather than mass gatherings of people. The sheer scale creates a unique aesthetic experience of awe and abstraction.

Spencer Tunick

Rineke Dijkstra: Activating Empathy and Social Cognition

While not exclusively nude, Rineke Dijkstra’s “Beach Portraits” are powerful studies in vulnerability that engage the brain’s empathy circuits. She captures adolescents in a transitional, often awkward state. Their slightly uncomfortable poses and direct, unshielded gazes are potent activators for our mirror neuron system and insula, allowing us to feel a shadow of their self-consciousness and fragility. Her work is a deep dive into social cognition, exploring how we perceive and relate to others during formative life stages, creating a deeply moving and psychologically resonant viewing experience.

Rineke Dijkstra

The Ethical Brain: The Responsibility of the Neuro-Informed Artist

Understanding the brain’s response to nude imagery underscores the power and responsibility of the photographer. This knowledge must be used ethically. It means using the power of the FBA to celebrate diverse body types, not just reinforce narrow standards that can create negative social comparison. It means being aware that the amygdala’s response can be tied to trauma, and that images should be created with respect for the viewer’s potential sensitivities. An ethical approach uses these insights not to manipulate, but to create deeper, more honest connections, always prioritizing the dignity of the subject and the well-being of the viewer.

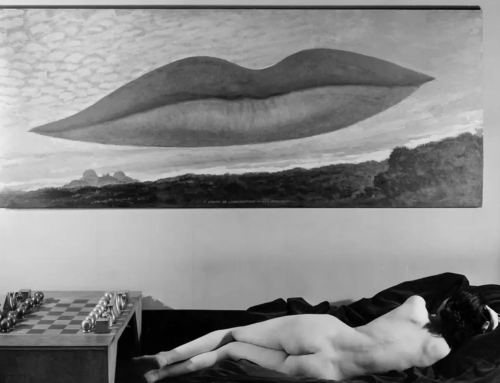

Ruth Bernhard

Conclusion: From Visuals to Brain States

Understanding the neuroscience behind nude art offers photographers a new layer of intentionality. By considering how the brain processes form, emotion, and beauty, we can move beyond intuition and make informed artistic choices that resonate on a deeper, neurological level. This interdisciplinary approach doesn’t remove the magic of art; it gives us a glimpse into the mechanics of that magic. The most powerful nude art often works on multiple levels – visual, emotional, and cognitive. By understanding these neurological processes, you can create images that don’t just capture the eye, but also engage the mind and connect with the viewer in a profound, lasting way.

The Artist’s Perspective: In his nude art photography workshops in Berlin, award-winning photographer Burak Bulut Yıldırım often explores how understanding viewer perception can enhance artistic impact. With nearly two decades of experience, he emphasizes how insights from neuroscience can help photographers create images that engage viewers more deeply and memorably.

Limited edition works by Burak Bulut Yıldırım are available for collectors on respected platforms such as Saatchi Art and Artsper. You can also explore his portfolio of contemporary projects at burakbulut.org.

To learn more about incorporating these concepts into your photography or to join a workshop that delves into the psychology of viewer engagement, connect with us on Instagram or email hello@nudeartworkshops.com.