The Camera in Her Hands: How Women Redefined Nude Art Photography

The history of nude art photography is inextricably linked with the history of looking. For much of its existence, the genre was overwhelmingly dominated by a singular perspective. This comprehensive exploration delves into the revolutionary work of women in nude photography who stepped behind the camera to dismantle that tradition, reclaiming the narrative of the body and transforming it from a mere object of beauty into a complex, powerful, and authentic subject.

The Canon and Its Discontents: Deconstructing the “Male Gaze”

To understand the magnitude of their contribution, we must first understand the world they entered. In her seminal 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the term “the male gaze.” She argued that in visual culture, women were traditionally positioned in a passive role, their bodies arranged and presented for the aesthetic and erotic pleasure of a presumed masculine, heterosexual viewer. This created an “active/male, passive/female” binary that was deeply embedded in Western art.

In 19th and early 20th-century nude photography, this was the default mode of operation. Women were often depicted as anonymous odalisques or mythological figures, their individuality stripped away to serve an idealized, classical vision of beauty. Photography, with its perceived realism, intensified this dynamic, creating images that felt less like artistic interpretations and more like objective truths. It was against this backdrop of objectification that women photographers began their quiet, and later explosive, revolution.

Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976): The Modernist Pioneer

Imogen Cunningham

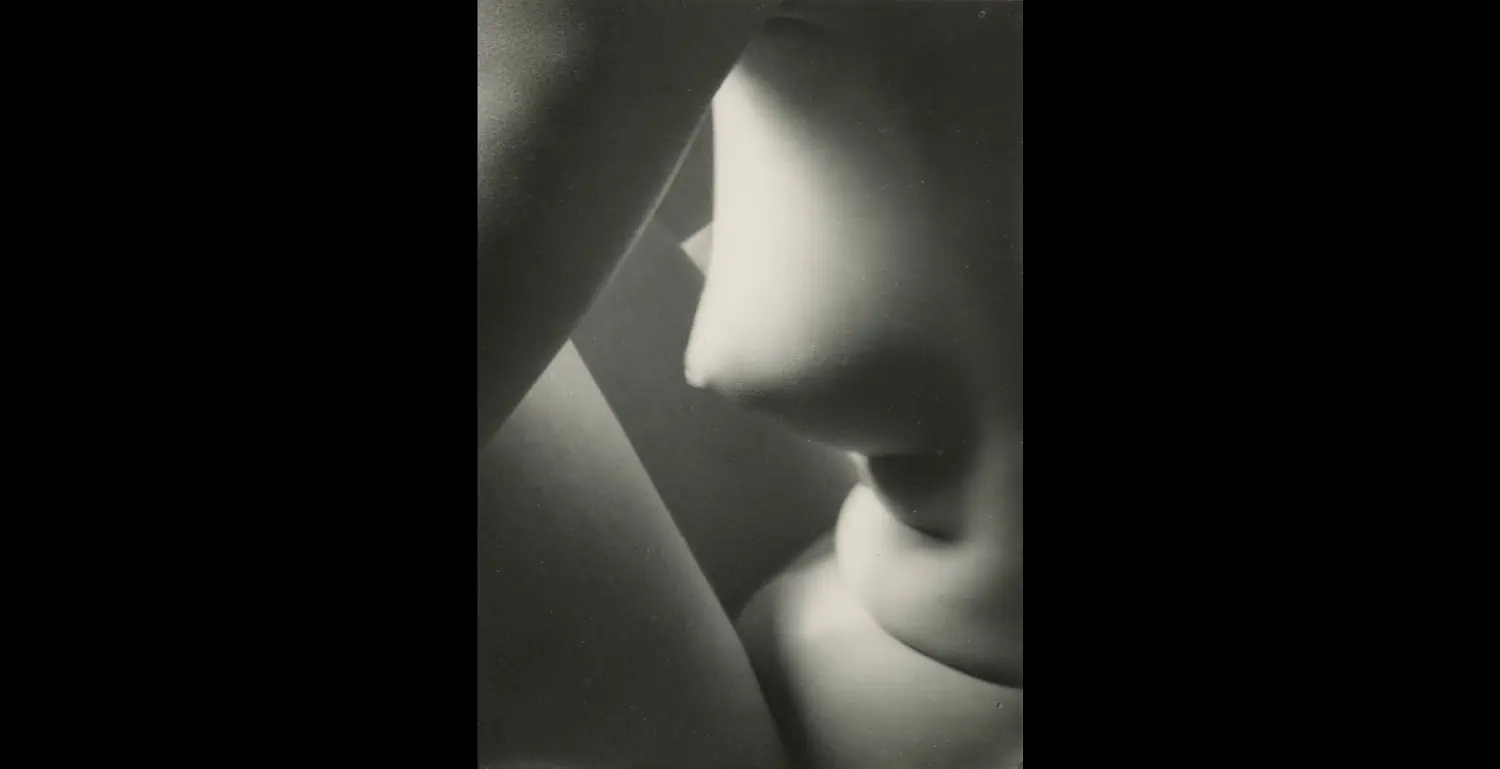

As one of the earliest and most influential female photographers to work with nudes, Imogen Cunningham’s approach was a radical departure from the norm. A member of the modernist Group f/64, she rejected the soft, romanticized style of Pictorialism in favor of sharp, clear focus and an emphasis on pure form.

From Pictorialism to f/64: A Shift to Pure Form

By applying the “straight photography” ethos to the body, Cunningham encouraged viewers to see it not as an erotic object, but as a fascinating subject of abstract and sculptural qualities. Her iconic image “Triangles” (1928) is a masterclass in this modernist approach. By tightly cropping a pregnant woman’s torso, she transforms the belly, breasts, and arms into a dynamic composition of intersecting geometric shapes. The identity of the subject is irrelevant; the focus is entirely on the beauty of the form itself.

“Triangles” (1928) by Imogen Cunningham

Yet, she was not only a formalist. “Two Sisters” (1928) offers a tender, soft-focus portrayal of two nude women resting together. The photograph is remarkable for its depiction of intimacy and non-performative vulnerability, presenting a vision of female connection that stands in stark contrast to the isolated, posed nudes created by her male contemporaries.

Diane Arbus (1923-1971): The Rejection of Glamour

Diane Arbus

While not exclusively a nude photographer, Diane Arbus’s raw, unflinching portraits often included nude subjects who existed far outside the conventional standards of beauty. Having started her career in the glamorous world of fashion photography with her husband, her personal work was a deliberate rebellion against that industry’s artifice. She was drawn to the unique, the unconventional, and the marginalized, photographing her subjects with a directness that could be both empathetic and unsettling.

The Unflinching Gaze and the Banal Nude

Her square-format, direct-flash imagery created a sense of stark confrontation. A prime example is “Retired man and his wife at home in a nudist camp…” (1963). This is a stark, honest portrayal of an ordinary elderly couple in their cluttered living room. The nudity is incidental, almost banal. By stripping away the eroticism and idealism typically associated with the nude, Arbus confronts the viewer with the unidealized realities of aging, domesticity, and long-term partnership. She radically expanded the scope of who could be considered a “proper” subject for a photograph, paving the way for a more inclusive, documentary-style approach.

“Retired man and his wife…” (1963) by Diane Arbus

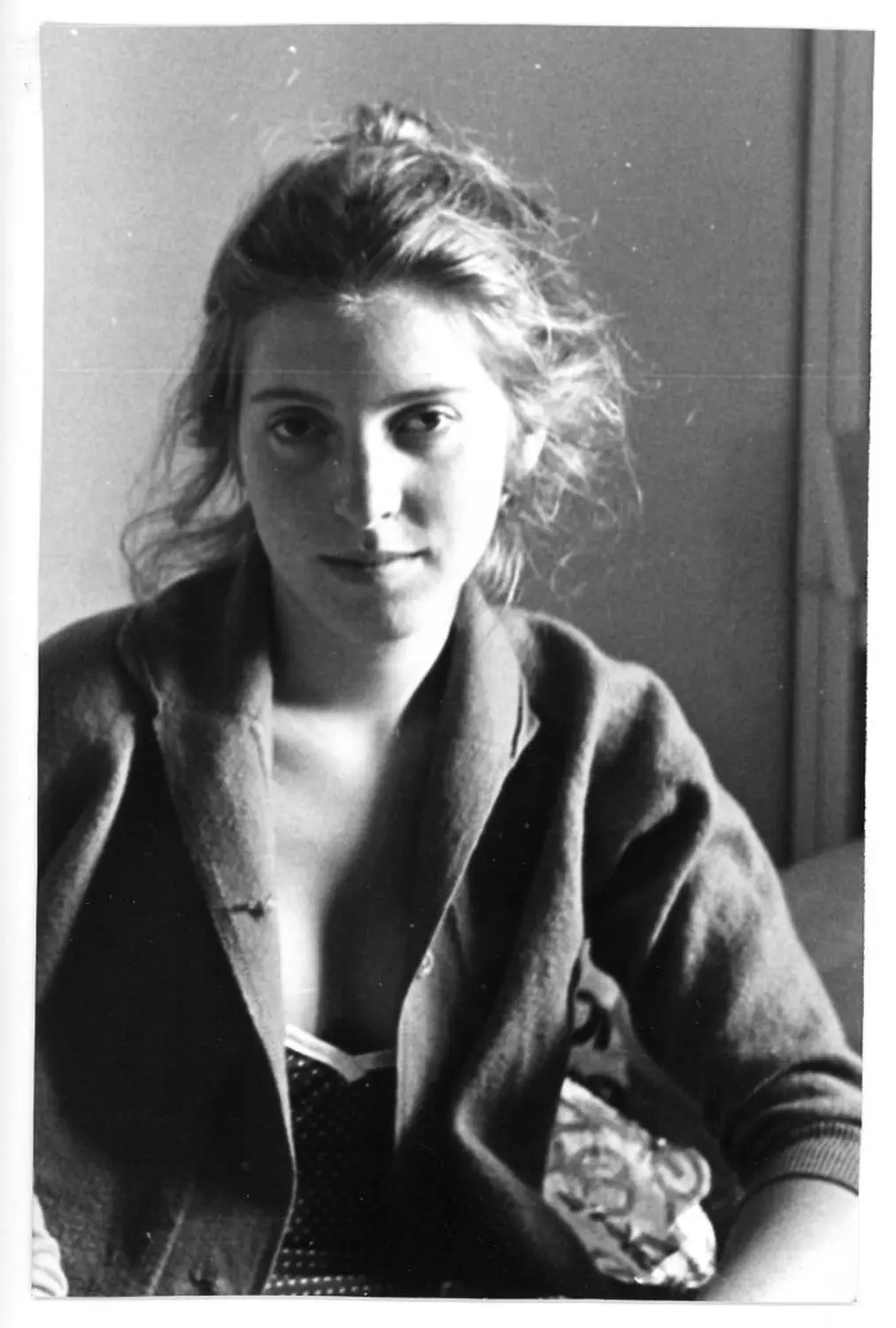

Francesca Woodman (1958-1981): The Body in Space

Francesca Woodman

Despite her tragically short career, Francesca Woodman left a lasting and profound impact. Using her own body as her primary subject, her surreal, haunting self-portraits explored themes of identity, the self, and the ephemeral nature of existence.

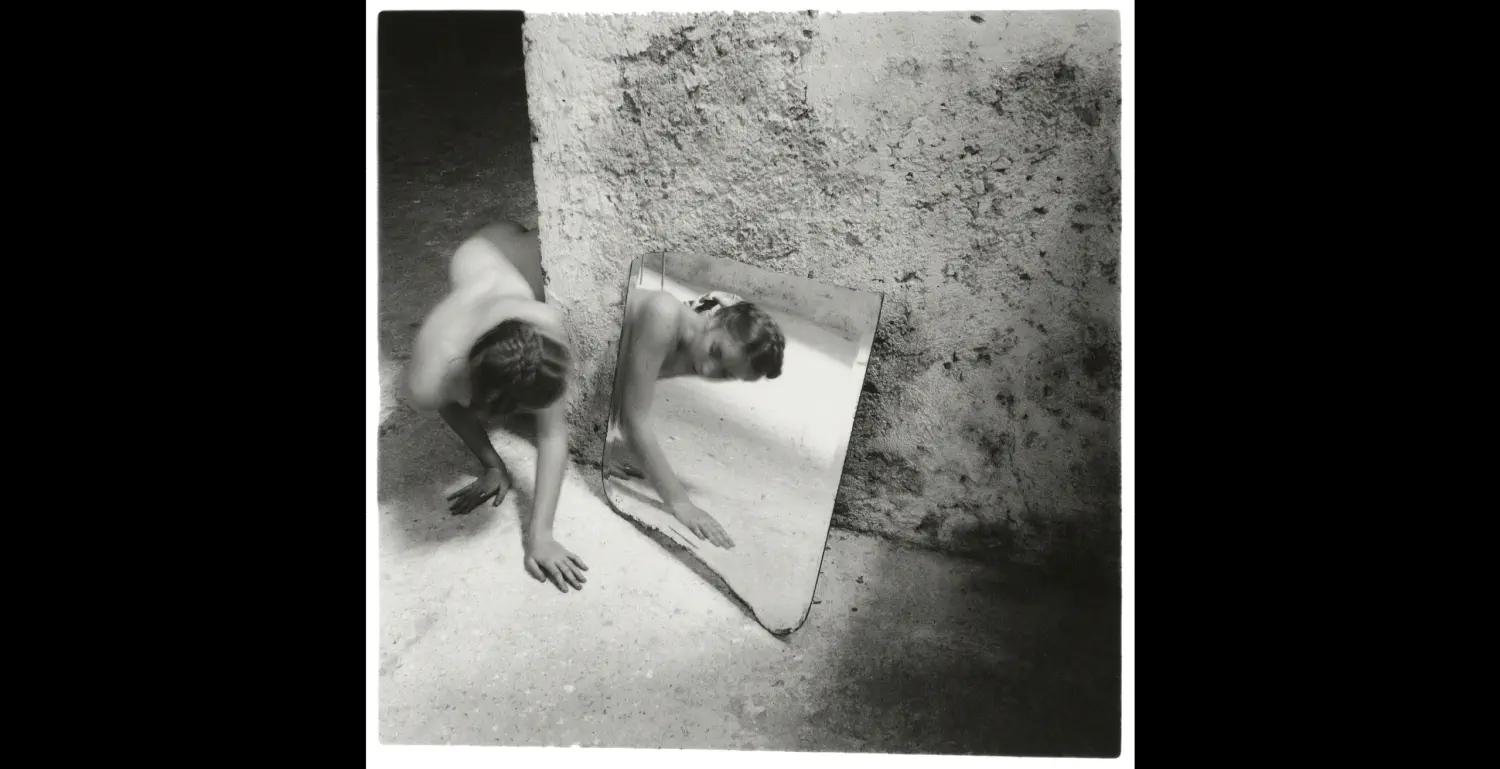

Performance, Surrealism, and the Gothic Self

Her nude form is rarely presented with confident stillness; instead, it is often a ghostly presence, blurred by long exposures, half-hidden behind furniture, or dissolving into the decaying architecture of her surroundings. Her work evokes a powerful sense of claustrophobia and a desperate search for a stable self. In “Self-deceit 1, Rome, Italy” (1978), she uses a mirror to fragment her own nude body, a powerful metaphor for the fractured and elusive nature of self-perception. In her “Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island” (1976) series, her ghostly figure seems to merge with the peeling wallpaper, visualizing a sense of fading away or being subsumed by one’s environment. Woodman’s intensely personal and conceptual approach has influenced generations of artists exploring the body, performance, and identity.

“Self-deceit 1” (1978) by Francesca Woodman

Cindy Sherman (1954-present): The Politics of the Pose

Cindy Sherman

Cindy Sherman’s work, in which she is always both artist and model, has been instrumental in deconstructing ideas of identity, representation, and the male gaze. By transforming herself into countless different female archetypes—the B-movie starlet, the society woman, the pin-up girl—she reveals how “femininity” is a constructed and often artificial performance.

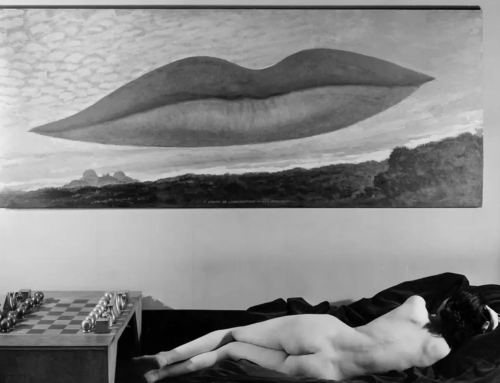

Subverting the Centerfold

In her landmark “Centerfolds” (1981) series, she was commissioned by a magazine to create pin-ups, but she subverted the request entirely. Using the large, horizontal format of a men’s magazine, she portrayed her characters not as sexually available, but as vulnerable, anxious, or lost in thought. The image below is deeply unsettling because it adopts the visual language of eroticism only to deny the viewer the expected payoff, making them acutely aware of their own voyeuristic expectations and the artifice of the pin-up trope.

From the “Centerfolds” series (1981) by Cindy Sherman

Sally Mann (1951-present): The Unflinching Matriarch

Sally Mann

Sally Mann’s intimate photographs have sparked important conversations about family, innocence, and the nature of art. She is renowned for her use of large-format cameras and the 19th-century wet-plate collodion process, whose inherent flaws imbue her work with a haunting, timeless quality.

The Maternal Gaze and the Male Form

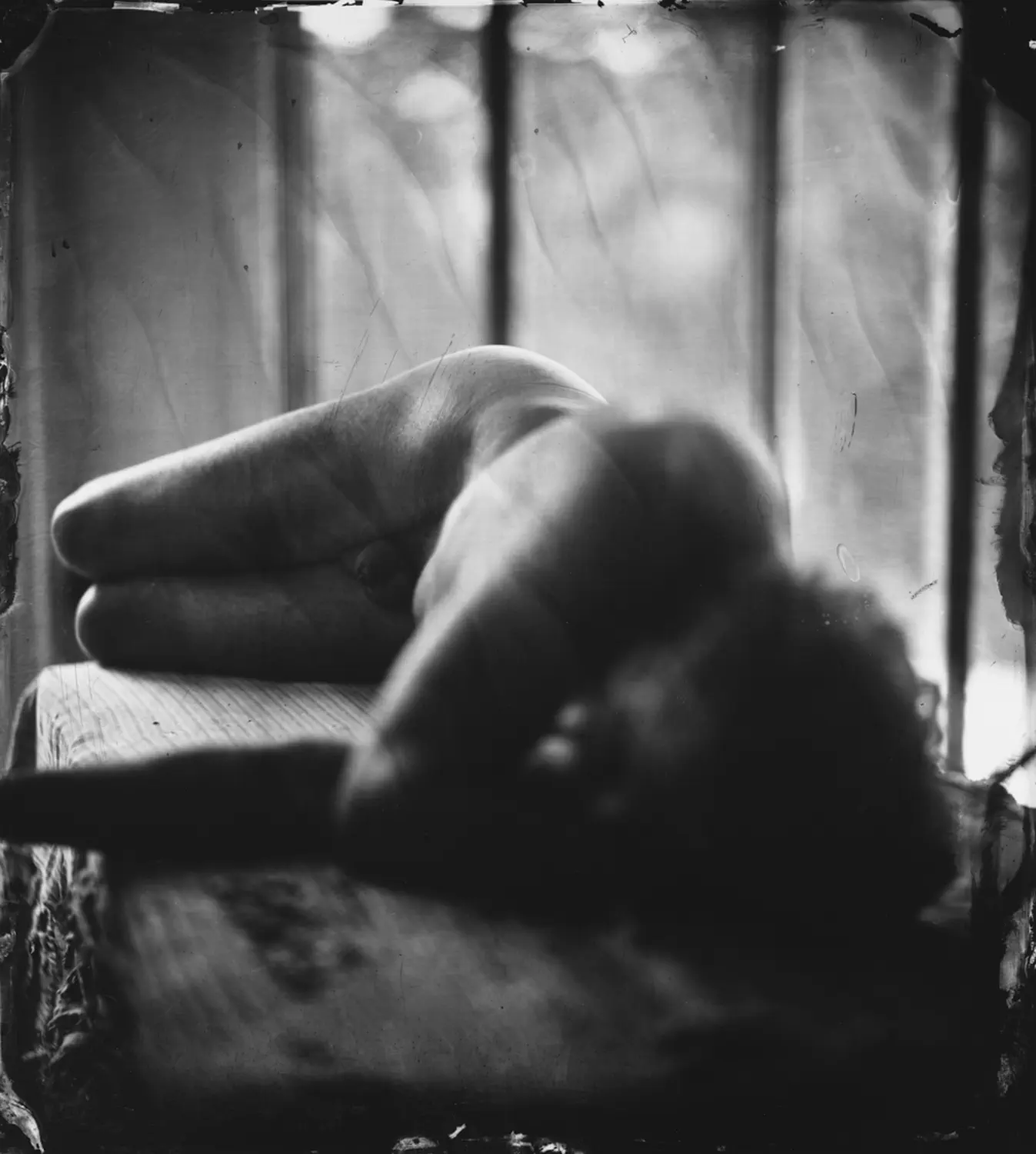

Her celebrated and controversial series “Immediate Family” (1984-1994) included nude photographs of her young children, igniting a fierce public debate. Years later, her series “Proud Flesh” (2003-2009) completely inverted the traditional gaze. It consisted of intensely intimate nude studies of her husband as he battled a debilitating illness. In the powerful image below, the male body is presented with a tenderness, vulnerability, and unflinching honesty that is rarely seen, offering a profound exploration of love, aging, and mortality from a distinctly female perspective.

From the “Proud Flesh” series (2003-2009) by Sally Mann

Rineke Dijkstra (1959-present): The Liminal State

Rineke Dijkstra

Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits offer a stark, honest, and deeply empathetic depiction of the human form during moments of significant life transition. Her “New Mothers” (1994) series consists of portraits of women shortly after giving birth. The women are nude from the waist down, their postpartum bodies shown with unflinching honesty. The image below is a powerful testament to the physical and emotional aftermath of childbirth, challenging centuries of idealized “Madonna and Child” imagery and giving visibility to a raw, rarely-depicted female experience.

From the “New Mothers” series (1994) by Rineke Dijkstra

The Contemporary Vanguard: Intersectionality and Global Perspectives

Contemporary women photographers are increasingly bringing intersectional perspectives to nude art, recognizing that experiences of gender are shaped by race, class, sexuality, and culture. Artists from diverse backgrounds are using the medium to explore the complexities of their unique experiences.

Zanele Muholi (1972-present): Visual Activism and the Black Queer Body

Zanele Muholi

South African visual activist Zanele Muholi’s work is dedicated to increasing the visibility of Black LGBTQIA+ identities. Their powerful self-portraits, such as in the series “Somnyama Ngonyama” (Hail the Dark Lioness), are a direct challenge to societal norms and a celebration of identities that have been historically erased. In these images, Muholi often uses everyday objects—like clothespins or scouring pads—to create elaborate costumes, directly referencing the history of domestic labor for Black women in South Africa while creating images of defiant, queenly beauty.

From the “Somnyama Ngonyama” series by Zanele Muholi

Lalla Essaydi (1956-present): Writing Back to the Canon

Moroccan-born Lalla Essaydi’s work directly confronts and dismantles the Orientalist depictions of Arab women created by 19th-century European male painters like Ingres and Delacroix. Her elaborate, large-scale photographs, such as those in her “Les Femmes du Maroc” series, reimagine these historical paintings. She replaces the passive, eroticized subjects with empowered women whose bodies and surroundings are covered in henna calligraphy, literally inscribing their own cultural identity and personal narratives over the top of the male fantasy.

From the “Les Femmes du Maroc” series (2005-2007) by Lalla Essaydi

Conclusion: From Object to Author

As we celebrate the contributions of women to nude art photography, we see a clear and powerful narrative arc: the transformation of the nude from a passive object to an active, complex subject. By dismantling the traditional male gaze and creating space for their own, women have fundamentally expanded what a nude photograph can be. Through their lenses, the body becomes a site for exploring identity, motherhood, trauma, power, and political resistance. The work of these pioneering and contemporary women continues to inspire new generations, challenging conventions and revealing new dimensions of the human experience. They have proven that the most compelling nude art often comes from authentic, personal perspectives, and by embracing their diverse voices, the entire genre of nude art photography continues to evolve in powerful and necessary ways.

The Artist’s Perspective: In the spirit of supporting this ongoing evolution, photographers like Burak Bulut Yıldırım have been instrumental in creating inclusive spaces for learning. His nude art photography workshops in Berlin actively encourage and support all artists, especially women, in finding their own voice. These workshops provide a safe, respectful environment for women to explore the genre, whether as photographers or models, and to develop an artistic vision that is uniquely their own.

For collectors, Yıldırım’s limited edition works are also available on respected platforms like Saatchi Art and Artsper, and his full portfolio can be seen at burakbulut.org.

To learn more about workshops designed to foster diverse perspectives and individual creativity, connect with us on Instagram or email hello@nudeartworkshops.com.